. . . but I think it doesn’t have the nerve to face him.

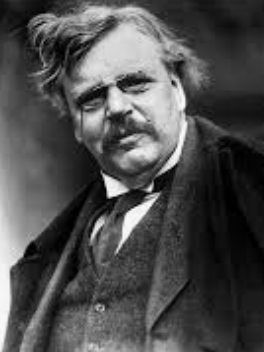

Gilbert Keith Chesterton (1874–1936) died 87 years ago today. A giant of a man and a giant of a writer and thinker, Chesterton wrote prolifically about politics, history, theology, culture, philosophy, literary criticism, and economics with his signature style of bracing insight, wit, reason, wonder, and brilliance. He also wrote poetry and fiction.

I picked up As I Was Saying: A Chesterton Reader in a Goodwill for about fifty cents about ten years ago. I had vaguely remembered reading quotes of his here and there and finding him interesting and funny. But as I read through the reader, I found myself feeling exhilarated and yet cheated at the same time. Who was this guy and why had I never really heard of him?

When my son was in ninth or tenth grade, I shared a library e-book of Chesterton’s Heretics with him, thinking he might appreciate GKC’s humor and masterful reasoning. Over the course of the next few days, I kept receiving random texts or emails from my son, written over his lunch hour or in spare moments in class, that simply contained quotes from the book—sometimes followed by an exclamation point. He was hooked. Since then, we’ve routinely given Chesterton books to each other for birthdays and Christmases and have built up quite a collection!

His body of work feels as fresh today as when it was first written. One of the reasons is because we’re living through exactly what he prophesied: the unraveling of the modern Enlightenment project and the fracturing of a common understanding of what human beings are and what we are for (i.e., what our end, or telos, is). He foresaw many of our current societal issues—and he realized that they all stem from our most basic assumptions about life and the cosmos. (Ideas have consequences.)

Another reason his work feels fresh is because he sounds so sane, so human, so full of wonder and joy and brilliance, as he helps us to see exactly what we need to see. He blusters into the stuffy, smoky room of our confused modern and postmodern minds, throws open the windows and lets in the striking sunlight and cool air, and splashes some cold water on our faces, all the while laughing uproariously at himself and at us.

Modern thinkers and commentators and critics have found it much more convenient to ignore Chesterton rather than to engage him in an argument, because to argue with Chesterton is to lose.

Dale Ahlquist, President of the Society of Gilbert Keith Chesterton

Almost anything Chesterton wrote is worth reading, but his magnum opus, The Everlasting Man, is essential. A popular book when it was published, it would probably be a tough read for many today. We’re not used to thinking broadly and freely and creatively and deeply about the essential questions of humankind and our history. Certain questions—particularly metaphysical ones—have been off-limits in the public sphere for too long. And our habits of sustained thinking and attention are rusty.

I’d love to challenge you, if you’re reading this, to wade in to the waters and give Everlasting Man a try (or, as a warm-up, start with Heretics and then Orthodoxy). Read with an open mind. Some of Chesterton’s dear friends (e.g., George Bernard Shaw, Bertrand Russell) were his opponents in public debates, and though they frequently found themselves defeated by his wit, wisdom, and reason, they remained affectionate and admiring friends of his.

The world is not thankful enough for G. K. Chesterton.

George Bernard Shaw

I, for one, am thankful for this brilliant man, and am honoring the anniversary of his death by sharing him with you.

I’ll leave you with a few GKC quotes:

The free man is not he who thinks all opinions equally true or false; that is not freedom but feeble-mindedness. The free man is he who sees the errors as clearly as he sees the truth.

Fallacies do not cease to be fallacies because they become fashions.

Most modern freedom is at root fear. It is not so much that we are too bold to endure rules; it is rather that we are too timid to endure responsibilities.

The Christian ideal has not been tried and found wanting; it has been found difficult and left untried.

Nobody has any business to use the word ‘progress’ unless he has a definite creed and a cast-iron code of morals. Nobody can be progressive without being doctrinal.

“Every true artist does feel, consciously or unconsciously, that he is touching transcendental truths; that his images are shadows of things seen through the veil.

The simplest truth about man is that he is a very strange being; almost in the sense of being a stranger on the earth. In all sobriety, he has much more of the external appearance of one bringing alien habits from another land than of a mere growth of this one. He cannot sleep in his own skin; he cannot trust his own instincts. He is at once a creator moving miraculous hands and fingers and a kind of cripple. He is wrapped in artificial bandages called clothes; he is propped on artificial crutches called furniture. His mind has the same doubtful liberties and the same wild limitations. Alone among the animals, he is shaken with the beautiful madness called laughter; as if he had caught sight of some secret in the very shape of the universe hidden from the universe itself. Alone among the animals he feels the need of averting his thought from the root realities of his own bodily being; of hiding them as in the presence of some higher possibility which creates the mystery of shame.